Why we love to lose ourselves in religion

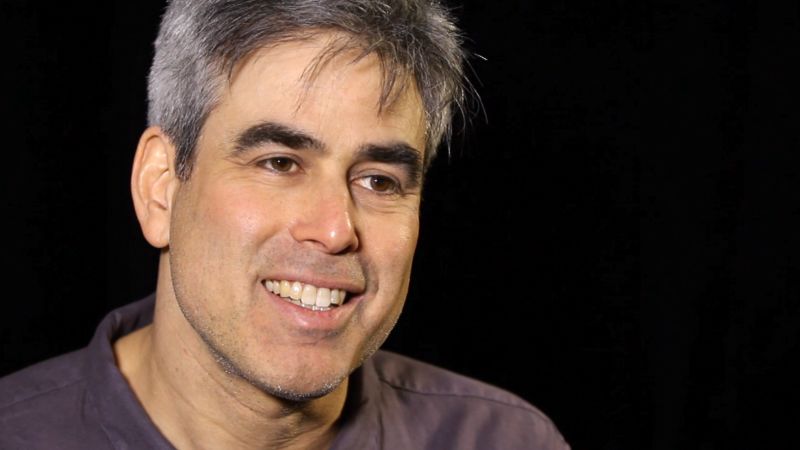

Editor’s Note: Jonathan Haidt is a professor of psychology at the University of Virginia, and a visiting professor of business ethics at the NYU-Stern School of Business. He is the author of a new book, “The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion”. He spoke at the TED2012 conference last month. TED is a nonprofit dedicated to “Ideas worth spreading,” which it makes available through talks posted on its website

Story highlights

Jonathan Haidt: Religion, like love and ethical action, offers a way to transcend the self

He says whether you believe or not, religion accomplishes the miracle of group inspiration

Haidt says religion’s ability to move people makes it an evolutionary advantage for groups

He says our minds evolved to be more religious in tandem with our cultures

CNN

—

What’s an atheist scientist like me doing writing good things about religion? I didn’t start out this way. As a teenager, I had contempt for religion. I was raised Jewish, but when I read the Bible, I was shocked. It hardly seemed to me like a good guide for ethical behavior in modern times, what with all the smiting and stoning and genocide, some of it ordered by God. In college, I read other holy books, and they didn’t make me any more positive toward religion.

In my 20s, I obtained a Ph.D. in social psychology and began to study morality. I ignored religion in my studies. We don’t need religion to be ethical, I thought. And yet, in almost every human society, religion has been intimately tied to ethics. Was that just a coincidence?

Watch Jonathan Haidt’s TED Talk

In my 30s, I began to study the emotion of “moral elevation.” That’s the warm, fuzzy feeling you get when you see acts of moral beauty. When you see someone do something kind, loyal, or heroic, you feel uplifted. You can feel yourself becoming a better person – at least for a few minutes.

Everyone who has watched an episode of Oprah knows the feeling, but there was absolutely no scientific research on this emotion. Studying moral elevation led me to study feelings of awe more generally, and before I knew it, I was trying to understand a whole class of positive emotions in which people feel as though they have somehow escaped from or “transcended” their normal, everyday, often petty self.

TED.com: Jonathan Haidt on the moral roots of liberals and conservatives

I was beginning to see connections between experiences as varied as falling in love, watching a sunset from a hilltop, singing in a church choir, and reading about a virtuous person. In all cases there’s a change to the self – a kind of opening to our higher, nobler possibilities.

As I tried to make sense of the psychology of these “self-transcendent emotions,” I began to realize that religions are often quite skilled at producing such feelings. Some use meditation, some use repetitive bowing or circling, some have people sing uplifting songs in unison.

Some religions build awe-inspiring buildings; most tell morally elevating stories. Some traditional shamanic rites even use natural drugs. But every known religion has some sort of rite or procedure for taking people out of their ordinary lives and opening them up to something larger than themselves.

It was almost as if there was an “off” switch for the self, buried deep in our minds, and the world’s religions were a thousand different ways of pressing the switch.

TED.com: Robert Wright on optimism

In my TED talk, I wanted to illustrate some of these experiences visually. Many scientists who write disparagingly about religion focus on the conscious, explicit beliefs in God and the supernatural. I wanted to shift attention away from that aspect of religion onto the more emotional and social aspects.

Whether or not you believe in God, religions accomplish something miraculous: They turn large numbers of people who are not kin into a group that is able to work together, trust each other, and help each other. They are living embodiments of e pluribus unum (From many, one). No other species on the planet has ever accomplished that. Bees and ants are great at it, but they can only do it because they are all sisters.

And this brings us to the most contentious question in the scientific study of religion: Is religiosity – including our tendency to believe in supernatural entities as well as our ability to lose ourselves in religious rites – an adaptation? Did we evolve to be religious?

TED.com: Billy Collins on everyday moments

Some biologists, such as Richard Dawkins (author of “The God Delusion”), argue that we did not. They say that religions are cultural inventions which are costly and destructive for individual believers. They say that religions only persist and spread because they get into our minds the way that a virus gets into our bodies. Once someone believes that he’ll be rewarded for recruiting converts and punished forever in hell for leaving the church, he tends to do things that help the church, even if they hurt him.

But I find another perspective much more compelling: Our minds evolved to be religious in tandem with our cultures. Cultures evolve in ways that are somewhat analogous to organisms: as long as groups are competing with each other, then features that foster survival and growth tend to spread; features that are self-destructive become less frequent.

What atheists can learn from religion

Cultural groups that found effective ways to bind non-kin together out-competed groups that were less cohesive. This is a view put forward originally by Charles Darwin, but revived in modern times by the biologists David Sloan Wilson, at Bimghamton University, and Edward O. Wilson, at Harvard. This is a view called “group selection,” because it argues that our genes came down to us today not just because some individuals were more fit than their neighbors, but because some groups were more fit (more cohesive and cooperative) than their neighboring groups.

I’ve spent my whole career trying to figure out what morality is and how human beings came to be moral creatures. Religion, I believe, is an essential piece of the puzzle. I’m still an atheist, but nowadays I’m one who finds a lot to admire in religion and in religious communities.

Follow us on Twitter: @CNNOpinion

Join us at Facebook/CNNOpinion